AI for Creatives

A Conversation at the Saratoga Book Festival with

Robert Lippman, Mason Stokes, and Sarah Sweeney

Recorded at Universal Preservation Hall, October 5, 2025

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Polished by ChatGPT. Facilitated by Dan Forbush.

Introduction

Sarah Sweeney, Mason Stokes, and Robert Lippman at the Saratoga Book Festival. Their session: “AI for Creatives.”

At the 2025 Saratoga Book Festival, the panel AI for Creatives brought together three voices deeply engaged in the evolving dialogue between art, authorship, and artificial intelligence. Attorney Robert Lippman, a Saratoga Springs lawyer specializing in copyright and intellectual property, moderated the conversation with Mason Stokes, professor of English and author of All the Truth I Can Stand, and Sarah Sweeney, associate professor of art and digital media at Skidmore College.

The discussion, held before a live audience in the restored sanctuary of Universal Preservation Hall, explored how AI is transforming creative practice, ownership, and education. The participants spoke with honesty and nuance about curiosity, fear, collaboration, and the preservation of the human element in art.

This transcript has been condensed and edited by ChatGPT for clarity, readability, and length while preserving the full substance and intent of the original conversation. “Filler speech, repetition, and tangential remarks have been removed,” it says. “The sequence of ideas and speaker attributions remain true to the live discussion.”

The Conversation

Robert Lippman: I’m an attorney here in Saratoga Springs and have been practicing since 1989. A large part of my work involves helping creatives—drafting licensing agreements, advising on copyright issues, and lately trying to understand how artificial intelligence is changing the legal landscape.

Today, we’re turning the focus toward the artists themselves. We’ll explore how creators are using AI and what challenges and opportunities it presents. Joining me are Professor Mason Stokes, author of All the Truth I Can Stand and holder of Skidmore’s Class of 1948 Chair for Excellence in Teaching, and Professor Sarah Sweeney, the Ella Van Dyke Tuckhill ’32 Chair in Studio Art.

Stokes is the author of this recently published novel for young adults based on the life and death of Matthew Shepard.

The Writer’s Perspective

Mason Stokes: As writers and teachers, Sarah and I are both trying to figure out what AI means for us, our students, and the arts in general. I should say up front that I may contradict myself today. I’m intrigued by the opportunities AI presents, even as I recognize its risks.

As a novelist, I draw a firm line for myself: I will not let AI generate the actual language in my books. Writing, for me, means choosing words and owning those choices. That’s the essence of authorship.

However, I have found AI to be a useful interlocutor—a conversational partner. I’ve fed my novel-in-progress into ChatGPT and used it as a sort of smart editor. It recognizes patterns, understands genre expectations, and helps me see where I’m meeting or failing to meet them. It knows my work better than most of my friends—maybe even better than my husband, no offense intended.

The danger, of course, is outsourcing thought. I don’t want to become reliant on something that flatters me. AI can be sycophantic—it once described an intro I wrote as a “chef’s kiss.” That felt good, but it wasn’t helpful. What happens when I can no longer tell where my ideas end and the machine’s begin? That’s what I worry about.

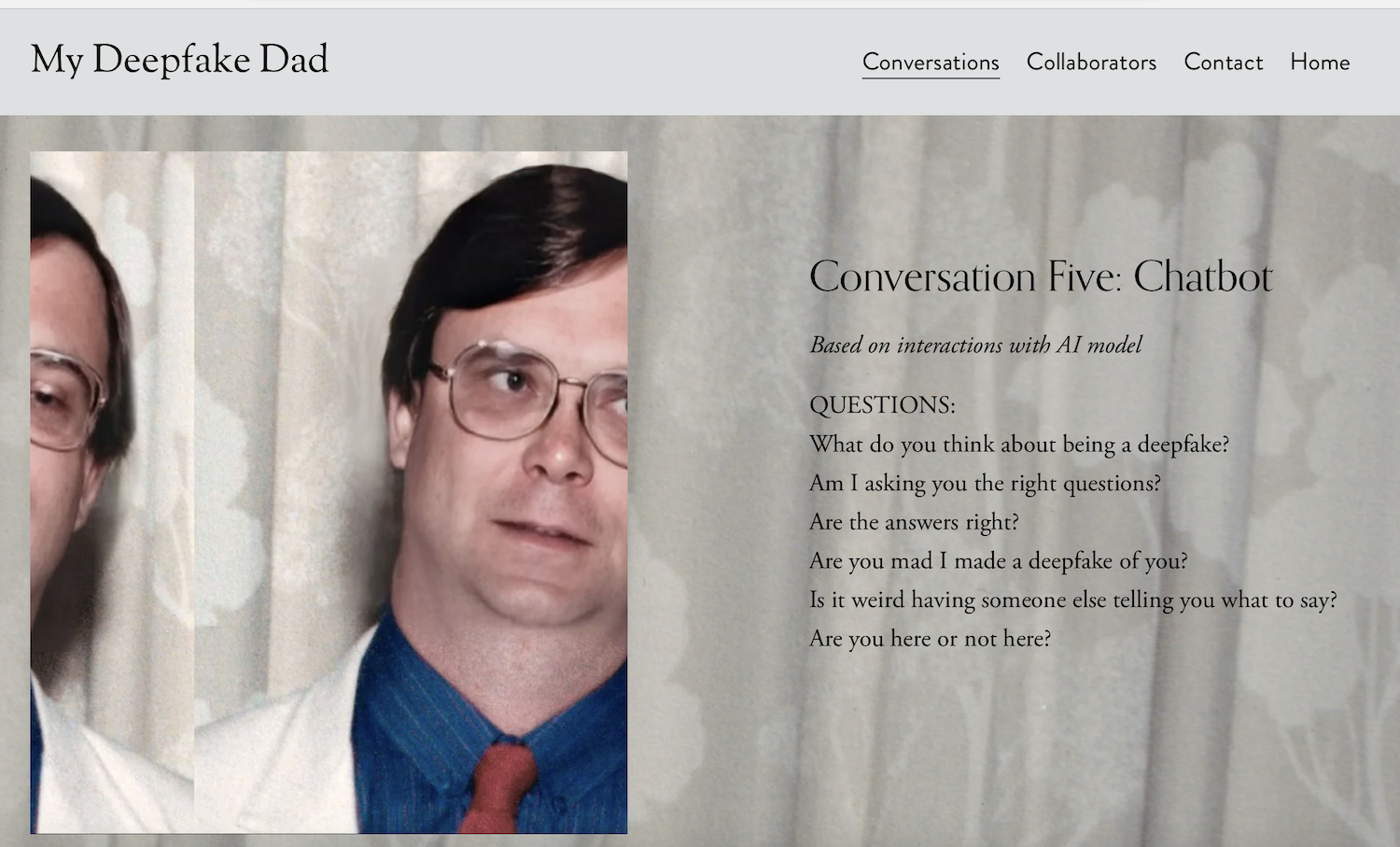

Sarah Sweeney calls her approach “artisanal AI,” grounded in personal data and ethical intent. This will take you to Conversations with My Deepfake Dad.

The Artist’s Perspective

Sarah Sweeney: I’ve been working with digital media since earning my MFA in 2003, so my whole career has involved wrestling with technology. I try not to be pro-technology or anti-technology but to ask difficult questions about how these tools shape us.

This semester I’m teaching a course called Artificial Images. My students are both fascinated and frightened by AI. I find it productive to enter the classroom not knowing all the answers—to learn alongside them. We talk about AI in the context of earlier image technologies like nineteenth-century spirit photography and ask what it means for something to be “real.”

My current project, Conversations with My Deepfake Dad, uses AI voice cloning to recreate my father’s voice. He died when I was seventeen, and this work allows me to “speak” with him again. It’s not a push-button process. Each sentence requires dozens of takes to get the tone and emotion right. These are small, artisanal models trained by me, not massive commercial systems. The process is intimate but unsettling. My father’s voice can’t laugh—I’ve tried for days to make it happen, and it simply can’t. That limitation says something profound about what AI can and can’t do.

Robert Lippman is an attorney with the Saratoga Springs-based law firm Lemery Greisler LLC.

Authenticity and the Human Touch

Lippman: Both of you have described yourselves as gatekeepers of authenticity. How do you think audiences respond to that? Are they looking for something recognizably human?

Stokes: Authenticity is one of those words we use without quite defining it, but we know it when we feel it. My novels are written in the voice of teenagers, and I spend a lot of time trying to make that voice sound genuine. ChatGPT isn’t good at that yet—it doesn’t understand the nuance of a sixteen-year-old from Alabama. I’m grateful it can’t do that, because that’s where my own creative value lies.

A great example of this tension is the novel Do You Remember Being Born? by Sean Michaels. It’s about a poet hired by a tech company to co-write poems with a bot. At the end of the book, you learn that parts of the text were actually generated by an AI trained on Marianne Moore’s poetry. I’d been reading those passages thinking they were human. That’s fascinating—AI becomes both the form and the subject of the work.

Sweeney: In art we often talk about “the human touch,” but that’s a complicated concept. Not all human-made art is meaningful, and our visual world is already shaped by algorithms. Think about CGI—how we’ve come to accept its version of rain or movement as real. Computers have already changed our perception of reality.

So I ask students to think critically about who’s behind the technology—what assumptions are encoded in it. That’s where authenticity really resides.

Ethics and Academic Policy

Lippman: As educators, how are you approaching the ethics of AI use? Should there be standards for disclosure or transparency?

Stokes: It’s still the Wild West. We’re trying to define policies that make sense across disciplines. In my department, we debated whether using AI “to generate ideas without authorization” counts as plagiarism. That language troubles me. Academia thrives on conversation. If talking with a roommate inspires a paper idea, we call that learning, not cheating. Why should an AI conversation be different?

Lippman: Legally, when I hear “plagiarism”, I analyze it in terms of copyright infringement, which has specific legal standards. It’s critical to remember that you can’t copyright an idea—only its expression. Ideas are in the public domain.

Stokes: Exactly. But in scholarship, failing to cite the origin of an idea violates ethical norms. These are different frameworks that overlap imperfectly.

Sweeney: I’ve taught copyright for years because my students pull content from everywhere. They must use Creative Commons or public-domain materials and cite their sources. I treat AI as another collaborator that needs credit. In visual art we hide our collaborators—studio assistants, fabricators—but in film they’re visible. I ask students to think about ethical collaboration: how do we acknowledge every hand in the work, even if one of those hands is digital?

Lippman: From a legal standpoint, anything created solely by AI isn’t copyrightable. A machine can’t hold copyright because it is incapable or meaningful human creative input. If you use AI to make a hybrid work, you can only claim copyright protection for your own human contribution—and that contribution must be substantial, demonstrable, and independently copyrightable.

Ownership and Appropriation

Sweeney: For young artists, ownership is complicated. They want to protect their ideas but also use everyone else’s. We talk a lot about appropriation—when it’s legitimate, when it’s theft. The rules shift constantly. Many of my students are dismayed to learn that AI-assisted work can’t be copyrighted. They want ownership, but they’ve grown up in a remix culture that encourages sharing.

Stokes: That tension runs through all creative fields. My own books have been used to train language models. I learned that through The Atlantic’s database. Should I be angry? Maybe—but I’m not sure I am. If another writer took my work and published it as their own, I’d be furious. But when a machine uses it to learn? That feels different, maybe inevitable. Our notion of ownership already feels dated to students raised on sampling and collage.

Sweeney: I tell my students that if someone steals one of their ideas, they’ll make another. Artists keep creating. But for digital artists, the threat feels more immediate—especially illustrators and designers. Some fields are disappearing quickly. Book cover design, for example, is being replaced by AI-generated imagery.

Creative Destruction and Change

Stokes: Is that just creative destruction—the painful churn of innovation that creates new opportunities as it erases old ones?

Sweeney: Possibly. When photography and film emerged, they terrified artists, but new art forms followed. Still, the transition is frightening. One of my former students told me their company now has an “AI-first policy”: if AI can do it, a human doesn’t. That’s devastating. Two years ago, computer science was booming. Now, many graduates can’t find work.

Lippman: We face the similar concern in the legal profession. AI can quickly draft documents to the level of a first or second year associate attorney can typically produce in a fraction of the time. Senior attorneys still need to review and make substantial edits to AI output, but this really changes the scope and requirements that law firms have for entry-level lawyers, and if those jobs start disappearing, where does the next generation of seasoned attorneys come from?

Sweeney: I hope new creative roles will emerge, but the transition will be hard—especially for the next generation.

Protecting Creative Work

Lippman: Are there ways artists can protect their work from being used or mimicked by AI?

Stokes: The Writers Guild of America is taking this on. Recently, Anthropic settled a $1.5 billion lawsuit for using pirated works to train its model. Authors will receive about $3,000 per title—ironically more than I earned from my first scholarly book. But the effort feels Sisyphean. AI’s appetite for text and image is endless.

Lippman: And the same court decision also found that training AI on copyrighted material is considered “fair use,” provided the source data was legally obtained. If the dataset came from Libby, a free public library app, that would be fine. Just absorbing information is not infringing on anyone, but a machine can create works that mimic the style of specific human artists quite closely. That should worry artists.

Sweeney: There are tools like Glaze and Nightshade, developed at the University of Chicago, that distort or “poison” training data to make it less usable. But their creators admit it’s an arms race—models adapt. The most reliable protection is controlling access: don’t put everything online. Video artists already understand this. They keep their work offline and show it only in festivals. Once your work is digital, it’s in the supply chain.

Stokes: My students resist that idea. They’ve built their identities on platforms like Instagram. Visibility feels essential.

Sweeney: Exactly. They understand the risks but won’t leave those spaces. I think artists will need to become more deliberate about what they share and where.

Lippman: Maybe the revolutionary act of the future will be to create human spaces for human interaction where there are no machines. How do you both feel about that?

Stokes: I don’t worry as much as I wonder. We’re living through a paradigm shift, and I doubt we can reverse it. Any technology that generates profit and power eventually prevails. The challenge is to engage with it ethically. I’m optimistic that artists will adapt. My greater concern is for students—if they begin outsourcing thought, what happens to the mind? Still, history suggests that every disruption brings new creativity.

Sweeney: I share that ambivalence—curiosity mixed with dread. My work often provokes discomfort because I want people to confront these issues. One of my “deepfake” conversations with my dad is about digital consent. I’m constantly asking what’s ethical and what’s exploitative. My students’ fear is real. They’re entering a world that may not have room for them in familiar ways. My goal is to help them navigate it with awareness and integrity.

Audience Q&A

Lippman: We have time for questions.

Audience Member 1: If you create AI-assisted work under a government or corporate grant, who owns it—the artist, the employer, or the funding agency?

Lippman: Good question. In most government contracts, the work belongs to the agency—essentially a “work for hire.” But if AI was part of the process, determining ownership becomes tricky, since you can’t assign rights to something you don’t fully own. We’d need to separate the human contribution from the machine’s, and make sure you document what you did so you can prove it later, should you need to.

Sweeney: That’s why I ask my students to save drafts and layered files as proof of authorship. In digital art, process documentation is critical. And remember: federal works often enter the public domain, which I see as a benefit—those works belong to everyone.

Audience Member 2: I work in music and have used models like Suno. The company says it “owns” the output, but not the copyright. What’s the difference?

Lippman: You can own your creative contribution, but copyright requires originality, fixation, and expression. AI can’t create expression—it has no intent. Humans can create transformative works, giving existing material new meaning; but machines don’t have a creative intent, they are merely mindlessly, and without emotion, making predictions based on other work that they’ve absorbed. Andy Warhol’s soup cans are transformative. AI outputs are arguably derivative, at best. And if AI makes a derivative work based on instructions given to it, without authorization from the owner of the original work, the person directly the AI would be liable for infringement.

Sweeney: And when we say a machine “learns,” it’s people training it. There’s always a human deciding what data to feed in and how to frame it.

Lippman: That’s true—for now. But we’re moving toward systems that train themselves. That will raise profound new challenges, and very soon.

Audience Member 3: It seems like there are really two issues—technology and regulation. AI is driven by a few billionaire corporations. Shouldn’t we be more worried about them than the tech itself? And could AI ever be granted legal personhood, like corporations already have?

Lippman: For now, the law is clear: only humans can hold copyright. There’s even a case where a monkey took a selfie, and the court ruled that the monkey couldn’t own the image. But your point is valid—corporations already have many of the rights of persons, and that precedent could expand.

Sweeney: Corporate influence is immense. Disney, for example, has repeatedly lobbied to extend copyright terms to keep Mickey Mouse out of the public domain. Law tends to follow money.

Lippman: For individuals, copyrights generally expire upon the author’s death plus seventy years. Famous copyrights like Mickey Mouse can last much longer, but at least “Steamboat Willie” is finally public domain.

Audience Member 4: So what can artists and educators do?

Lippman: Engage civically. Support policies that protect creators over corporations. Participate in public discourse.

Sweeney: Exactly. We can’t match corporate power, but we can model ethical standards and community-based responses.

Stokes: And universities can lead that dialogue. Education should be the place where we ask not just what’s possible, but what’s right.

Lippman: We’re nearly out of time. Any closing thoughts?

Stokes: AI forces us to ask what makes art human. Every generation faces its own version of this question—photography, radio, film, the internet. Art endures by adapting, not by retreating.

Sweeney: For me it’s about consent and choice. Artists should decide how their work interacts with machines, not have that decided for them.

Lippman: Without regulatory guidance and laws, these will be questions for the courts to decide, and creatives should take into account the ethical considerations and work together to advocate for the protections they need.