A Man Who Would Not Stop Learning

Gerald Stulc was born in 1947, north of Prague. His grandfather had gone to Iowa and married a farm girl. They lived there for a time and then went back to the new Czechoslovakia. That is where his father, Jaroslav, was raised. He was born in America and carried an American passport.

As a member of the Academy for Lifelong Learning for the last ten years, Gerald Stulc has found the perfect forum for his love of teaching. He has taught courses on the Plague, the history of military medicine, World War I, World Was II, the biology of aging, and the art of anatomy. A painter with a special interest in naval history, he produced this depiction of the Battle of the Nile, a decisive naval engagement fought between the British Royal Navy and the French Navy in 1798. 1798. This fall he’ll teach seven classes on the history of China, from oracle bones to the modern state. He also serves as ALL’s chair.

The Nazis took him for a spy. They put him in a concentration camp. He lived, but it marked him. Emilie, his wife, worked in civil defense for the Germans. Both knew what it meant to survive.

Then came the Communists. In February 1948 they seized the country. Jaroslav and Emilie fled. Gerald was still a child. He was carried out as the borders closed.

Jaroslav returned to Czechoslovakia despite the danger because distant relatives were still there, and family ties pulled at him.

Stulc's grandfather was a minister in Cedar Rapids before he and his wife moved to the new Czechoslovakia. That’s why his father returned there following his arrest.

By the time they reached Cedar Rapids, Gerald was three. He spoke no English. In first grade he began to learn the language of the land that was his own by birth but still foreign to him.

He remembers visiting his grandmother in Prague in 1968. She greeted them in an Iowa accent, wearing an apron, feeding her chickens. "It was like entering The Twilight Zone," he says. “She had lived through Nazis, tanks, Communists, and still spoke as if she had left Cedar Rapids only yesterday.”

The Nerd

“I was truly a nerd,” he says. In junior high he spent his weekends in the library. He combed the card catalog, chased books, cursed when one was checked out. He studied medical history in the eighth grade. He memorized every aircraft of the Great War. Fokker D3. Fokker D7. Nieuport. SPAD.

His father loved history. His mother wanted to be a nurse. They kept a German medical book in the house, filled with illustrations. “I loved those anatomical illustrations,” he says. “I was like four or five years old. Either I grow up to be a famous surgeon or a famous serial killer,” he joked. He chose surgery.

The Surgeon

Stulc practiced surgery for 30 years before retiring in 2014.

The University of Iowa gave him his degree in medicine. Georgetown gave him his scars. He worked in transplant surgery in Chicago, in oncology in Buffalo. His days were long. His nights were longer. “My first night on call… I had never started an IV in my life. That night I had to start eighteen.” By the morning he was empty. He says of those years: “You learn by drinking from a fire hose.”

He worked under Adrian Kantrowitz in Detroit. Kantrowitz was ready to transplant a human heart. South Africa beat him to the record books. Gerald assisted in those rooms, touched those organs, stitched the torn seams of men and women who should not have lived but did.

“There isn’t a square inch of the human body I haven’t seen and laid hands upon, externally and internally, at virtually every age, in good health and in every conceivable presentation of disease and trauma,” he says.

The Navy

For 16 years, he served as a surgeon in the Naval Reserve.

He joined the Navy Reserve. Sixteen years. He wore the silver bird of a captain. He studied at the Naval War College. Clausewitz was his companion. He was attached to Marine rifle companies for combat drills. They told him to hit the dirt. He dove into mud. They laughed, but they respected him.

The Marines called him “Doc.” They learned he would flop down in the mud like they did. “Doc, you’re pretty good at that.” He grinned. “I’ve been doing this since I was a kid.”

He never went to Vietnam. His number in the draft lottery was one. But he was deferred. He treated veterans in Buffalo, worked the VA wards, heard their stories. Merrill’s Marauders. Guadalcanal. Europe. Asia. The real things.

The Writer

He burned out. The papers and the politics did not suit him. His wife, Diana, told him to try writing. “As usual, she was right,” he says. He earned an MFA in Creative Writing. He wrote at night.

His novel The Surgeon’s Mate came in 2018. It was about a boy on a British ship at Trafalgar, a surgeon’s assistant, scared and young. “Every single bit of the book that describes surgery or wounds are things I’ve experienced myself. It’s not made up.”

He wrote Celadon, the true story of a journalist who married a monk, lost a leg, studied ceramics, and died falsely accused in an American jail. An agent told him it would not sell. He put it under the bed. He is bringing it back.

Now he writes The Canvas Within. It is about art and anatomy, how man has seen his own body. He says a cave painting at Lascaux shows a man with a spinal cord injury. He believes this painting, crude and old, was the first spark of medical art.

The Teacher

For the Academy for Liberal Learning course he taught on the Plague, Stulc opened his first class in the guise of a plague doctor.

He loves to teach. “My passion is to teach, because I got all this information in my head till it hurts and I feel like I want to share.” He started at the Academy for Lifelong Learning in 2015. His first course was on plagues. He wore a black robe, a mask with a beak. He walked into the room as a plague doctor. Students laughed. They never forgot.

He has taught the history of military medicine. World War I. World War II. Art and anatomy. Biology of aging. This fall he'll teaches six classes on the history of China. He will speak of the Yellow Emperor and Confucius, the Han, the Song, the Ming. He'll lead the class from oracle bones to the modern state.

He believes in the classroom, in faces and eyes. Zoom does not work for him. “If I’m in a group and I say something witty, I see the expressions, the laughter. On Zoom, there’s just dead silence and automatically it flops.”

The Leader

In 2022 Empire State College cut ties with A.L.L. “They threw us out after 30 years,” he says. The classrooms, the offices, the support—gone. They scrambled for space in church basements, senior centers, the Knights of Columbus hall.

He was already on the board. The chair stepped down. The phone rang. “How would you like to be the next chairman?” He laughed. “It’s like the military. Everybody takes a step back, and you’re the one standing out in front.” He accepted. He still holds the post. He guides the group as they rebuild their numbers, their spirit, their home.

The Renaissance Man

He paints. He plays guitar. He is with the Albany Guitar Ensemble, working on Bach. He gardens, he dives, he collects old books and relics. He lectures on scurvy and naval medicine. He reads Clausewitz for pleasure. He is married forty-five years to Diana. He jokes about it. They have two sons. One is a lawyer in New York. The other left Hollywood to become an engineer.

He says he is wary of artificial intelligence. “I don’t know where it’s going to take us. It’s a brave new world. I’m excited about it at the same time.” He uses it for research. For stubborn sentences. “Three out of four times it comes up with something better.” But he worries. “I want to be creative. I don’t want a machine doing it for me. All art tries to give a perspective on the human condition. How can a machine do that?”

Offered the opportunity on a trip to Thailand to connect with a tiger, Stulc couldn't resist.

The Point

He has seen war, disease, surgery, life, and death. He has read history and written it. He has played music and painted. He has led others to learn. He is still learning himself.

He was a boy in Prague. A refugee in Iowa. A surgeon in Washington. A captain in the Navy. An author at his desk. A teacher in Saratoga. He is all of these things, and he is still moving forward.

He will keep teaching until the end. “Learning is what keeps us alive and human,” he says.

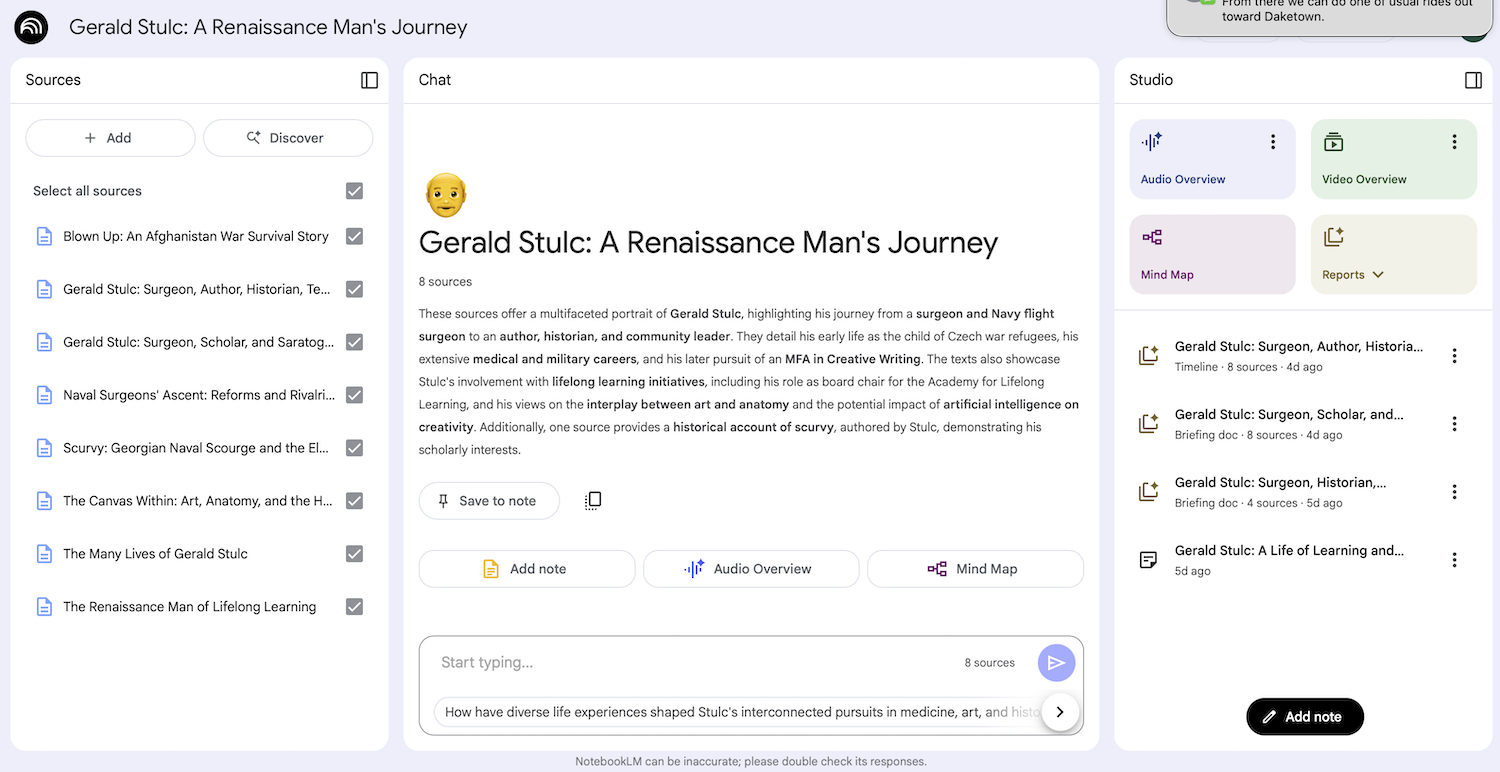

Crediting AI

This article was generated in the Smartacus Neural Net from a two-hour interview conducted with Stulc by Dan Forbush, Bill Walker, and Dominic Giordano, plus an additional seven sources we uploaded to our “GeraldBot” in NotebookLM. We prompted NotebookLM and ChatGPT to collaborate in writing this feature in the style of Ernest Hemingway because Stulc told us he’s his favorite author. We describe our process here.