The Supervisor & the City

A Salute to Matt Veitch

with some help from AI

I took on this assignment for three reasons:

Drawing on the six sources you’ll see listed in the column at left, NotebookLM produced the profile, video, and audio you’ll find below. (Click to enlarge.)

The Saratoga Torch Club will honor Matt Veitch on Monday, December 15 for his nine terms on the Saratoga County Board of Supervisors. You may reserve seats for this dinner here.

I’ve always respected Matt for his ability to work “across the aisle.”

I figured that telling Matt’s story would be a good way to demonstrate the power of AI in supporting a new form of civic journalism.

I didn’t write the stories you’ll find in multimedia on this page, but I did:

conduct the 90-minute interview with Matt on which these stores are mostly based;

upload the transcript of our conversation into NotebookLM as well as the results of a ChatGPT “deep search” and four other sources, including this profile published on The Faces of Saratoga Springs and a YouTube video of Matt’s presentation on the history of conventions in Saratoga Springs;

write prompts for NotebookLM and ChatGPT that generated these stories.

When we use AI in ways that mimic humans, I we must be upfront about we’re doing. Hence this intro.

AI at Work

Having aggregated all of the content I uploaded, NotebookLM will regenerate it in any form I wish. I chose three.

View this Video

Hear this Podcast

Read this Q&A

The Supervisor & the City

Some public figures define an era through rhetoric or confrontation. Matthew E. Veitch did it through steadiness. Over eighteen years as a Saratoga County supervisor, the fifth-generation Saratogian became a quiet architect of the region’s civic landscape—expanding trails and open space, modernizing policy, repairing county–city relations, and confronting the complicated chapters of local history that his own family helped shape.

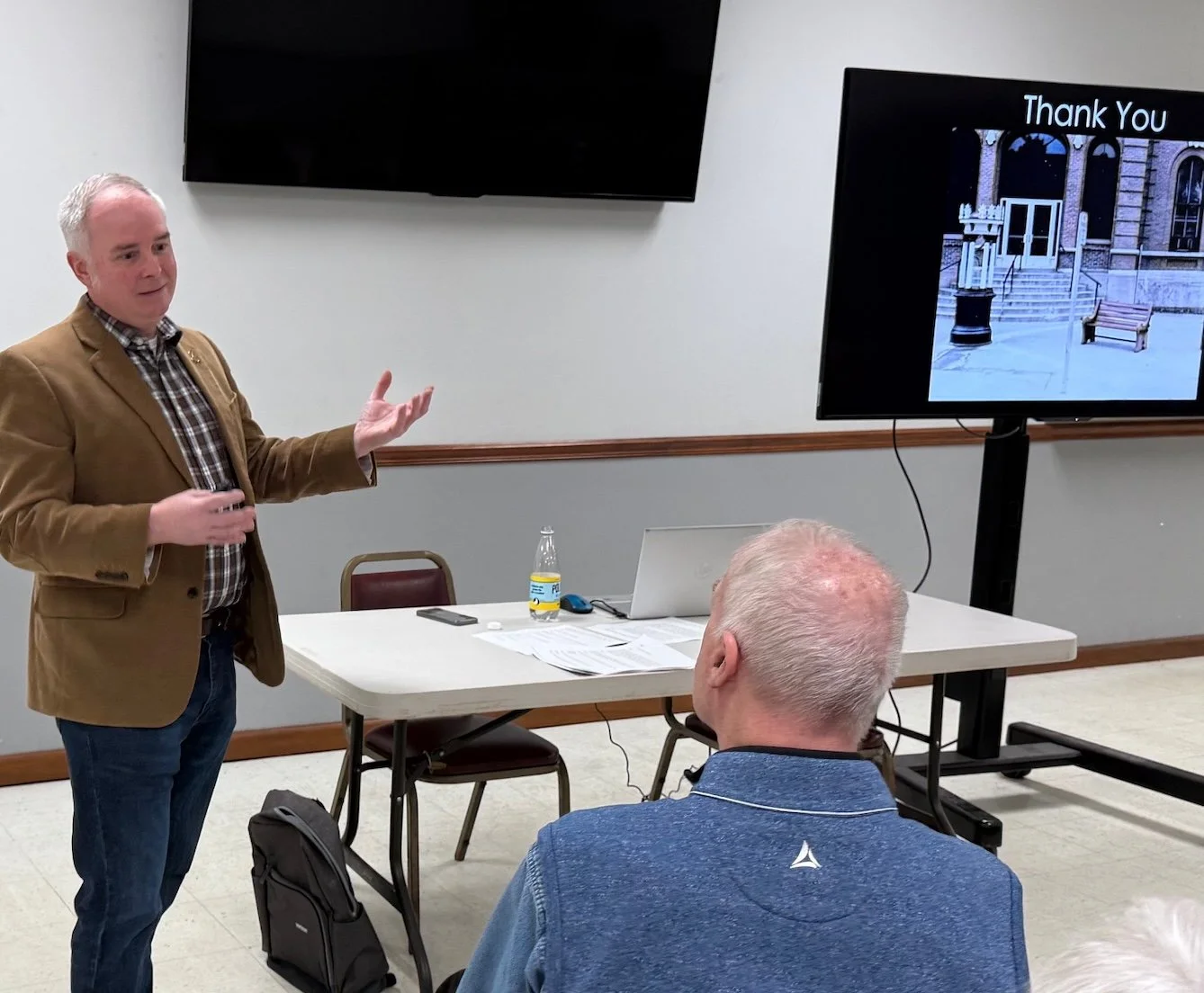

Lecturing in the Academy for Lifelong Learning’s Monday Speaker Series earlier this month, Matt Veitch spoke on the history of urban renewal in Saratoga Springs, a 25-year intiative directed by his grandfather,

His approach emerged early. The Geyser Road Trail, his first major public project, taught him that local government advances the way trails do: inch by inch, through engineering, planning, and persistence. As a supervisor, he brought that same patience to county work. He pushed for the creation of the Trails Committee, built support for open-space preservation, and helped turn former industrial land into the Graphite Range Community Forest.

“Compromise is not a bad word,” he has often said, and his politics reflected that belief—layered, incremental, and durable.

That steadiness mattered most in repairing the long-strained relationship between Saratoga Springs and Saratoga County. Under Veitch’s influence, funding flowed back to city priorities: a third fire station, a new EMS facility, an updated occupancy tax, and the permanent Code Blue shelter. The progress was slow, but lasting.

“Some things I started ten years ago are just finishing now,” he noted, a reminder that local government depends on people who stay long enough to see projects through.

His steadiness also shaped his approach to urban renewal, a complicated chapter of his family’s past. His grandfather directed the program that solved catastrophic flooding but erased a Black neighborhood. Instead of distancing himself, Veitch studied the record—photos, maps, property files—and acknowledged the full story. Now, as Saratoga’s City Historian, he is placing markers on Congress Street and the west side to honor the communities that were displaced.

Veitch leaves elected office but not public life. He is now CEO of the Saratoga County Capital Resource Corporation and custodian of the city’s archives. His colleagues describe his departure as the close of an era defined less by performance than by persistence. In a city built in layers—springs under stone, new streets over old ones—Veitch has been a steady line through those layers, helping Saratoga grow without losing track of what came before.

What follows is an edited transcript of our conversation, offering his insights in his own words.

How far back does your family’s Saratoga story go?

Now home to the Olde Bryan Inn, this was the Veitch family home for decades.

It goes back at least five generations, though it’s probably farther—we just haven’t fully documented beyond the early 20th century. The first solid evidence is in the 1920 and 1930 censuses, where you see my great-great-grandfather and his family living in Saratoga Springs. They were tied to the track. My great-great-grandfather was a steeplechase owner, trainer, and jockey, and all the sons went into the horse business—trainers, jockeys, everything.

My great-uncle, Sylvester Veitch, became a Hall of Fame trainer. His son, John Veitch, trained Alydar in those famous Triple Crown races in the 1970s. So the racing connection is really how we came to Saratoga.

On the other side of the family is Burnham’s Hand Laundry, which occupied what later became the Olde Bryan Inn. Family lore—unconfirmed but very believable—is that the Veitch boys brought their jockey silks to Burnham’s, met my great-great-grandmother there, and eventually the families merged. That building became the Veitch family home for decades. My dad grew up there, and I remember family gatherings in what’s now the outdoor seating area of the restaurant

How did this family background shape your interest in public service?

Public service was just part of our life. My grandfather ran Urban Renewal. My father taught at the high school. My cousin Kevin is now the supervisor in Greenfield. My brothers have served in DPW and the police department; one was police chief. So the dinner table was always about City Hall—who was in office, what issues were on the table. It was impossible not to absorb that.

Even before I ran for anything, I followed city politics closely. And when I married Stephanie McDonald—who I met downtown, not through politics—I learned afterward she was Roy McDonald’s daughter. I’d followed his career for years. He’s one of the people who encouraged me to think about running myself

How did the Geyser Road Trail become your first major project?

When I moved to Geyser Crest about 25 years ago, I ran right into the neighborhood’s biggest problem: no sidewalks, no safe way to get to the school or the park across the street, and a county road with heavy traffic running between everything. I grew up downtown, where you could walk everywhere. Out here, you couldn’t walk anywhere.

It took 15 years and $3.8 million to complete, but the Geyser Road Trail finally opened on April 22, 2021. It runs 2.8 miles from the Milton town line to Route 50 at Saratoga Springs State Park.

I read a story about neighbors organizing for pedestrian access. I wrote a letter supporting them, and two days later they called and asked me to join. I eventually chaired the committee.

We knew if we just handed the idea to the city, it would die—too expensive, too much bureaucracy. So the Neighborhood Association raised money, applied for grants, and hired engineers to create every scoping and feasibility document ourselves. Assemblyman Jim Tedisco helped with early state funding. State Parks contributed too. By the time we presented it to the city, it was shovel-ready.

It still took about 15 years total, start to finish. But now you can walk from my house to the school, to Veterans Memorial Park, all the way to the State Park, and up to Milton—without being on Geyser Road. It fundamentally changed how this part of the city works.

That project gave me name recognition—and practice. I was on the Zoning Board of Appeals at the same time, so people saw me in action. It all helped when I eventually ran for office.

What prompted you to run for County Supervisor?

A combination of timing, involvement, and encouragement from people like Mayor Mike Lenz and, indirectly, Roy McDonald. In 2005, all Republicans were swept off the city council for the first time. I joined the Republican committee and decided to run for one of the two supervisor seats.

I campaigned on quality-of-life issues—trails, open space—and on restoring a constructive relationship with Saratoga County, because at that time the city and county were not working well together. Saratoga Springs had left the sales tax agreement and opted out of the county water plan. Everything was confrontational.

I won in 2007, coming in second, and that launched 18 years on the board.

How did you create the Trails and Open Space Committee at the county level?

I pushed for it my first year, but the county didn’t want to put real money into it. So we worked out a compromise: instead of funding big projects, we’d start by using county-owned forest lands—old logging parcels with skid trails—and convert them into public trails.

Veitch has supported the development of trails and open-space preservation since joining the County Board of Supervisors in 2007, including a $100,0o0 grant toward the establishment of Pitney Meadows Community Farm.

The first was the Louden Trail near Wilton Mall. It was a hit. That success let us keep going. By the time I left the chairmanship, we’d opened about seven miles of county trails, and now the county is actually acquiring land—like the Graphite Range Community Forest—to build full trail systems. That evolution would have been unimaginable when I started.

Persistence is everything. You keep beating the drum calmly and reasonably, and ten years later the county is doing things it wouldn’t touch when you began.

What policy accomplishments stand out to you?

Updating the county occupancy tax is one. Back in 2015, when I chaired the board, I first raised the issue: Airbnbs were exploding yet only lodging facilities with four or more units were taxed. Hotels paid the tax; short-term rentals didn’t.

There was strong resistance—not just locally, but at the state level. Legislators don’t like being associated with “raising taxes.” I brought it up year after year. Just one month before my final meeting, the county finally passed the updated law. That’s the arc of county government: slow, deliberate, and dependent on people who stick around long enough to finish what they start.

A lot of the work takes five, ten, or fifteen years. If everybody cycles out after one term, nothing reaches completion. In recent years, the city council has had so much turnover there’s almost no long-term memory left at the table. That puts heavy pressure on staff and creates big gaps in procedure, policy, and history.

For the past four years, even though I wasn’t a commissioner, I was often the one saying, “In 2009 we talked about this,” or “In 2012 we agreed about that.” That’s the role of long-serving officials: you carry the institutional story so the community doesn’t have to reinvent itself every election cycle.

What draws you to the history of urban renewal?

Partly my grandfather’s role and partly my own preservation background. There’s a tension there: I believe in preserving historic built environments, yet my grandfather oversaw the demolition of entire neighborhoods.

Veitch lectured on the history of urban renewal in Saratoga Springs earlier this month in the Academy for Lifelong Learning’s Monday Speaker Series.

But you have to understand the era. This wasn’t unique to Saratoga; it was nationwide. Some decisions had racial impacts; some had racial intentions; but it’s too simplistic to call it 100 percent racist or 100 percent beneficial. The truth is in the middle. It solved some legitimate problems and created others, especially for Black residents and low-income households.

What Saratoga did exceptionally well was record-keeping. They documented almost everything—photos, maps, inventories. That allows us to have an informed debate today. And in many ways, our preservation movement and parts of our social justice movement grew out of that experience.

Why step down after 18 years?

Partly because I completed 25 years at Verizon and decided it was time for a career change. After leaving Verizon, I had time to think, and I realized I had accomplished what I set out to do in county government: the Geyser Trail, the trails committee, major open space projects, the occupancy tax reform, and a good working relationship between the city and the county. It felt like the right moment for someone else to take the seat and put their stamp on the job.

What roles will you continue to hold in public life?

Two major ones. First, I was just appointed Saratoga Springs City Historian. I’ve been in the office for two days and feel like I want to open every box—and also not touch anything because it’s all so delicate. The collection is incredible: village records from the 1800s, tax books, photographs, ledgers, Grand Union Hotel registers. It’s like a miniature museum hidden inside the Visitor Center.

My goals are to learn more history myself, help residents with questions about houses or family histories, digitize as much as possible, and launch a public-facing social media presence so people can see the city’s photographic history.

Second, I’ll become CEO of the Saratoga County Capital Resource Corporation. We provide tax-exempt bond financing for nonprofits—projects like Saratoga Hospital’s ER expansion, Raymond Watkin Apartments, Skidmore’s Tisch Learning Center, and the new BOCES facility at Exit 16. It’s niche but meaningful work.

What do you see as the major issues facing Saratoga’s future?

Homelessness is the biggest unresolved one for the city. The county’s Ballston Avenue Code Blue building helps, but it’s a seasonal solution to a year-round problem. Future supervisors will need to bring the city and county together in a way we haven’t fully achieved yet.

At the county level, the challenge is balancing economic growth with quality of life. GlobalFoundries changed everything. Malta, Halfmoon, Clifton Park—they’re enormous economic engines now. We have to avoid the mistakes of downstate suburbs: overbuilding, losing open space, losing identity. Open space and trails are central to that balance.